The Evolution of Irish Cuisine

By Shauna Driscoll

When we think of Irish culture, and especially Irish cuisine, one particular image usually springs to mind; that of the Irish farmer cultivating his potato crop to ensure a bountiful fall harvest. In fact, this image could not be further from the truth.

While the potato certainly has become a hallmark of Irish tradition, it is a relatively new produce for the Irish, and is in fact not native to their lands. This root vegetable was brought to Ireland from South America during the mid-17th century. It is only in the past few hundred years that the potato has become the icon of Irish heritage that we see today.

Since its introduction the potato quickly became a staple food item among the poor classes, due mostly to its ease of growth and storage, its heartiness in the often poor Irish soil and the many essential vitamins it was able to provide to the daily diet. This trend still exists today in traditional Irish dishes like colcannon and boxty. But, what was their diet like before this new foodstuff came into their possession?

Further back in history the Irish subsisted mostly on large and small game animals, and other products readily found throughout their territories. Deer, for instance, would be cooked within large holes cut in the ground that were filled with water. The water was then heated by the introduction of hot stones, and the meat boiled in a long process throughout the day.

Smaller game animals were frequently roasted over fires. In the earliest known histories, poultry was covered in a thick coating of clay, skin and feathers intact. The clay wrapped poultry was then placed into the fires until the clay was baked into a solid covering which was broken and peeled away, bringing the feathers and skin with it and exposing the moist meat within.

As production methods grew more organized, cattle, sheep and pigs were raised to feed the burgeoning population. However, these sources of food were mostly reserved for the higher classes who could afford such things, leaving the poor to make do with milk, butter, cheese and offal (the edible, mainly internal organs of an animal), often complimented by oats and barley, and a wide range of wild nuts and berries. In earlier times it is believed seeds of knotgrass and goosefoot may have been used to make porridge as a hot, sustaining meal.

With the introduction of the potato the poorer classes now had an easy crop that was useful in a variety of ways. Supplemented with buttermilk it formed the basis of the Irish diet, and it was also useful in fattening pigs that would be slaughtered and then cured for winter storage.

Unfortunately, this reliance on the potato crop also meant that a poor season would affect those classes more severely, leaving them starving and unable to sustain themselves throughout the winter months. And it was during one of these times, the Potato Blight of 1846 – 1849, that approximately 2 million Irish citizens emigrated from their homeland in an effort to find better fortunes abroad.

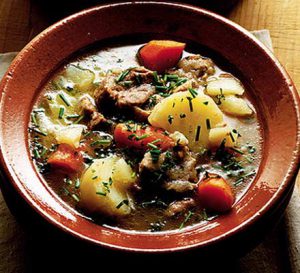

Traditional Irish Stew

These emigrants brought with them their signature cuisine and cooking style, although not everything could remain as it was. Irish Stew, for instance, is made solely from lamb or mutton meat. Sheep were widely raised for wool clothing, milk for drinking and cheeses, and later used as a food item along with other easily found or grown ingredients.

Once they reached the New World the Irish were not able to continue all of these traditions. Foodstuffs that grew plentiful, or were raised easily, like sheep, were not readily found in America. Over time their traditional dishes had to change and evolve to include the native plants and animals.

Corned Beef and Cabbage Dinner

A prime example of this, the traditional Easter supper in Ireland most commonly consisted of boiled bacon and cabbage, as pork was more readily available to the poorer classes than any other meat product. In America the traditional Easter supper of those poor emigrants who found their way to the New World was adapted to the new environment they found themselves within. With beef, especially the poorer cuts which were tenderized by “corning” them in a brine solution, being the more prominent and less expensive meat source, the traditional boiled dinner became the one now associated with St. Patrick celebrations in North America: corned beef and cabbage.

We continue to see the evidence of this Irish emigration throughout out modern culture in North America. The large influx of Irish in the 18th and 19th centuries has had significant influence not only on North American cuisine but also on the assortment of celebratory drinks we gained from other cultures to have arrived in the New World.

Bunratty Mead

One of the oldest alcoholic beverages to be produced in the world comes from Ireland in the form of mead, a honey wine traditionally served before the start of a meal and to end a feast. It was a common addition to any celebration and festival, and was used as a gift for newlyweds. An offering of a month’s supply of mead (one full lunar cycle) was thought to bring good fortune to the couple. This practice is believed to have led to the well-known idea of a couple being on their ‘honeymoon’ bearing with them a sweet honey wine for the duration of an entire lunar cycle.

Coming from an often damp country, the Irish are also well known for developing other spirits and liquors that were either served on their own, or mixed with a variety of different cold and hot beverages to chase away the chill. Mulled wines, whiskey and ales were most commonly found for such purposes.

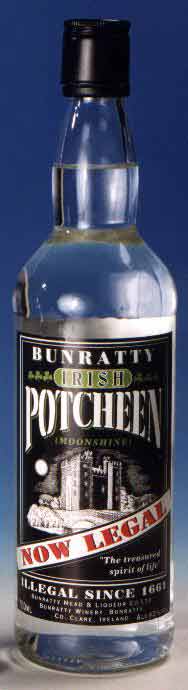

Bunratty Potcheen

For those who couldn’t afford such luxuries as whiskey and wine, the ever industrious and ingenious Irish found a way to make their own out of a fermentation of potatoes. The result of this process, “potcheen”, is now made commercially however it doesn’t carry quite the same “kick” as the home-made variety still being clandestinely produced in some of the more isolated regions of Ireland.

At some point during the 1940s, a group of American travelers arriving at the Shannon International Airport on a miserable winter evening were treated to an Irish coffee, a beverage created on the spot in an effort to warm the weary group. It quickly made its way to San Francisco, a city that shares similarities to the Irish climate, and has since spread as a popular drink in North American restaurants.

Two of the most common potato dishes that have traveled across the Atlantic with the Irish are boxty, a savory pancake made with potatoes and onions, and colcannon, a wonderfully comforting Irish dish that includes mashed potatoes, cabbage and onions. Although it may not be authentically Irish, I also include bacon in my recipe for colcannon. Here are recipes that you can try for a little taste of Irish cuisine.

Ingredients:

– 1/2 pound raw potatoes

– 1/2 pound leftover, unseasoned mashed potatoes

– 1 mdeium onion, finely chopped

– 1/2 pound flour

– 1 egg, slightly beaten

– salt and pepper to taste

– milk

Preparation:

Mix the grated and mashed potatoes with the onion. Stir in the flour and egg. Preheat lightly greased griddle or frying pan. Add enough milk to potato mixture for a thin enough batter that will drop from a spoon.

Use a 1/4 cup measurer to spoon out batter onto griddle. Grill for 3-4 minutes on each side.

They can be served with tart applesauce or as part of an Ulster Fry with bacon, fried sausage, fried eggs, and black pudding and soda bread.

Ingredients:

– 3 pounds russet potatoes

– 1 Tbsp. olive oil

– 1 small onion, diced

– 2 cloves garlic, minced

– 3 cups shredded cabbage (or kale)

– kosher salt and pepper to taste

– 1/4 cup butter, divided

– 1/3 cup half and half

– 2 slices pre-cooked bacon, warmed according to package directions and crumbled

Preparation:

Peel and dice potatoes. Place in a large pot and cover with water by one inch. Bring to a boil, covered, over high heat.

Remove cover, reduce heat to medium, and allow potatoes to cook 12-15 minutes, until tender when pierced with a fork.

Meanwhile, heat olive oil in a large skillet. Add onion and garlic. Cook, stirring occasionally, until onion is softened, about 3 minutes.

Add cabbage, season with salt and pepper, and cook until soft, about 5 minutes.

Drain potatoes and return to pot. Season with salt and pepper. Add two tablespoons of the butter and the half and half. Mash.

Fold in the cabbage mixture and the bacon. Top with the remaining butter. Serve immediately.

Summary:

Undoubtedly there are many cultures that have helped to shape our North American history, but perhaps one of the strongest influences of them all can be traced back to Irish immigrants, who hoped to make a better life in the New World. We see the markings of their contributions through so many of our own traditions: hearty soups and stews; boiled dinners; hot drinks served with liquor to take the chill off cold bodies during long winters; the ‘honeymoon’ time for newly married couples.

It is a mark that has seeped deep into our common heritage as we continue to build our identities apart from our ancestral lands. It brings with it a sense of comfort and well-being. And it has helped to ensure that even when we settled so far away from our people, we still managed to bring with us a piece of home.

_________________________________________________

Bibliography

A History of Irish Cuisine – www.ravensgard.org/prdunham/irishfood.html

Wikipedia – en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irish_cuisine

Great Food – www.greatfood.ie

Wikipedia – en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irish_coffee

Recipes – www.about.com/food