Representative Settlements – Planned and Unplanned

Johnville

Almost exclusively, the men and women who responded to Sweeny’s call for settlers were Irish immigrants, or their children. Most were from Sweeny’s own diocese, particularly Saint John, but many others came from as far away as Maine, Massachusetts, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and Ontario.

Though many were unprepared for the harsh realities of pioneer life, and would leave, disillusioned and disheartened, in the beginning they all saw past the obstacles to the possibilities, to the promise of a better life for themselves and their children and the vision of an independence they never dreamed of in Ireland.

The powerful forces that drew them to the upper reaches of Carleton County had their roots in events that pre-dated Sweeny’s settlement project by many years. The pioneering settlers of Johnville were part of a massive Irish immigration that fundamentally changed nineteenth century New Brunswick society. Though many fanned out into the rural areas of the province, most, lacking the resources to set themselves up on the land, stayed clustered in the cities, particularly Saint John.

Sadly, for many of these immigrants, conditions in the New World were little better than those they had left behind. Marginalized socially, economically and politically, they huddled together in ramshackle slums, eking out subsistence-level livelihoods by the sweat of their brows. With grinding poverty came the accompanying problems of disease, crime, and social unrest. The yoke of poverty turned out to be as oppressive in the New World as in the Old.

Bishop John Sweeny

Fired with a profound concern for his impoverished countrymen and a passionate yearning to see their dreams of a better life realized, Sweeny embarked on a “back to the land” campaign. A mesmerizing speaker, he took every opportunity to expound on his vision, travelling extensively throughout the Maritimes and New England, and even across the Atlantic. He told one such audience,

…” I have seen settlements of prosperous farmers in this country who have now arrived at comfort and independence, [though] they commenced in the heart of the forest in its natural state with little means to help them. They endured many hardships … but those who have been sober, industrious and persevering have succeeded in obtaining for themselves an honest and respectable independence.

I have seen their children grow up around them healthy and robust, inured to honest labour, and the aged parents in their declining years … see their children settled around them, independent farmers like themselves…. The labouring man who settled in the country has a house of his own, with the pure air of heaven circulating around …”1

The timing of Sweeny’s efforts was propitious. Government officials were equally desirous of establishing new settlers on the land. Legislation had recently been enacted providing more favourable conditions for land settlement and eventual ownership. The Bishop lost no time in taking advantage of this situation.

His negotiations with the Crown Land Office led to the surveying of blocks of land in several areas of the province. The first Johnville survey, carried out in May 1860, embraced some 10,000 acres in northeastern Carleton County. The positive response led to additional surveys, culminating in the Chapmanville survey in 1878, Sweeny’s attempt to relocate those who had been devastated by the Great Saint John Fire of June 1877.

No monetary payment was required for the land. It was free to any man over eighteen, not owning land already. If a man had sons eighteen or older, each of them was also entitled to 100 acres, adjoining that of his father if he so wished. Friends could petition for adjoining lots as well. Certain conditions had to be fulfilled before ownership was granted. The petitioner had to live on the land for a year, clear at least five acres in that time, plant at least three acres, and erect a log or frame dwelling no smaller than 16 by 20 feet. He was also required to do roadwork to the value of $60, at his convenience, within four years. Those terms having been met, the land was his, free and clear.

In all, 37,000 acres were surveyed and set aside for the Johnville area settlements under the aegis of the Emigrant Aid Society. Sweeny put Father Thomas Connolly, the Woodstock priest, in charge of the fledgling community. Connolly was a Saint John native, born there in 1823, the son of Irish immigrants. It was he who dubbed the place “Johnville”.

Sweeney has chosen well. Connolly not only possessed enthusiasm and sound judgement, but a practical knowledge of pioneer life as well. He welcomed the newly arrived, no doubt apprehensive, honesteaders, offering advice and encouragement. He supervised the dispersement of the lots and the layout of the roads and bridges. His assistance even extended to demonstrations of how to chop down a tree! Often he had to supplement the meagre food and clothing supplies that some of the settlers had brought with them.

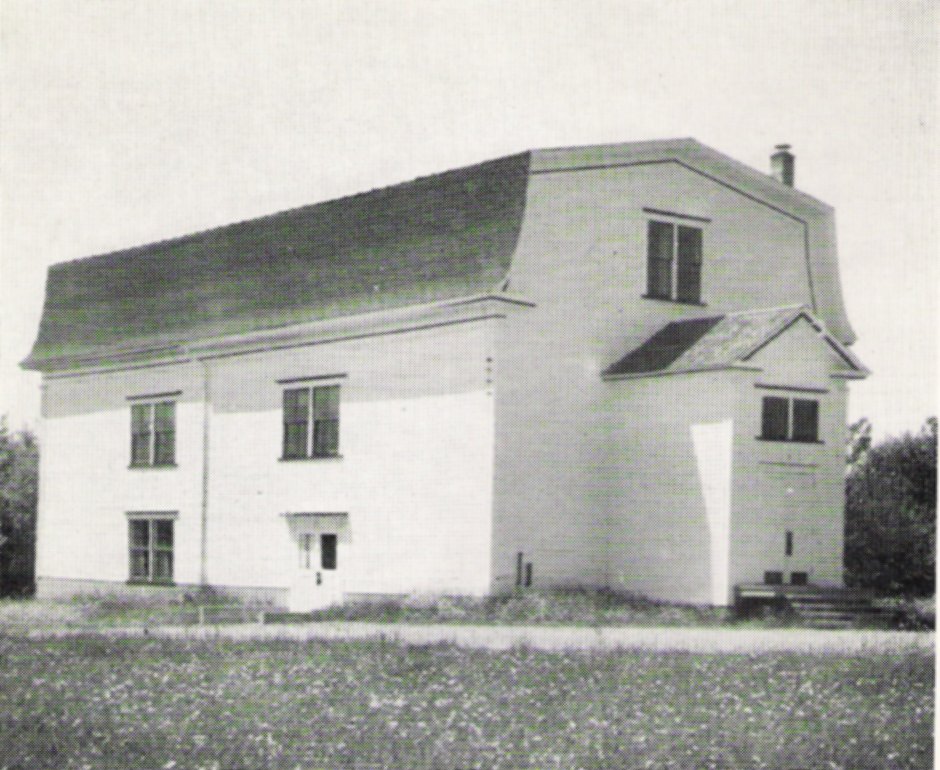

Father Connolly offered the first Johnville Mass in June 1862, in a clearing in the woods, where the church would eventually stand. He even brought his choir up from Woodstock! The same year Connolly oversaw the establishment of a school – a log structure on the Gallagher farm, and the following year, designed and supervised construction of the first Johnville church. It was Connolly who suggested “a modest basket picnic” to help raise funds to outfit the new church, thus establishing a tradition that would endure for well over a century. with no political or religious infrastructure yet in place, Connolly’s hands-on involvement gave the settlement the impetus it needed to get off the ground.

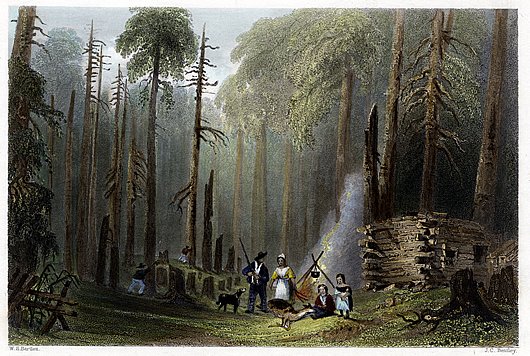

The early years were hard ones. For men, women and their children, the toil was arduous and never-ending, and the amenities few. Pioneer life was not for the weak of back, of will, or of spirit. But one tree at a time, one rock at a time, one fence post at a time, homes sprang up in the heart of the forest and patches of wilderness were transformed into ordered fields – their fields. The dream began to take shape.

By October 1866, when Irish writer John McGuire visited the place with Bishop Sweeny, the population of the settlement had risen to “about 600 souls. ” McGuire reported that despite the severity of the lifestyle and the lack of physical comforts, a spirit of optimism and hope prevailed.

Of course, not everyone who came to the shores of the Monquart stayed, but each passing year brought new settlers. Census figures for 1881 showed 1204 Catholics in the Parish of Kent, ten times as many as were living there twenty years earlier. More than one out of every three people in the Parish was Irish-born.

Bound together by a common ethnicity, a shared faith and by common circumstances and aspirations, the settlement evolved into a cohesive community. Where once they had experienced alienation and scorn, they now felt solidarity and empowerment. Little attempt was made to assimilate into the broader surrounding community. Especially during the early years, they clung to their Irish customs and traditions, even their language. Visitors to the community reported that Gaelic was nearly as commonly spoken as English. Even years after their arrival, they kept abreast of events in their homeland. By keeping alive the music, the history, the literature, and above all, the faith that comprised their cultural heritage, they further strengthened the ties that bound them together.

More than eighty per cent of the original petitioners were Irish-born. Each of the four corners of Ireland was represented, but by far the greatest number of settlers hailed from the northern province of Ulster, particularly County Donegal. A high degree of inter-marriage during the formative years resulted in an intricate networking among the founding families that further strengthened the sense of community. This attachment to community was so strong that many who died far afield, and had not lived in Johnville for years, were returned there for burial. Most of the present day population are the fifth, sixth or even seventh generation of the original settlers.

Along with the various sociological ties was a profound connection to the land itself. Land was life-affirming, nurturing, and eternal. Many of them had brought a handful of Irish soil, bundled up in a handkerchief, with them to the “America.” Land was independence. It was the legacy you bequeathed to your children. To an Irishman, 100 acres must have seemed like a kingdom.

However, the single most unifying force was unquestionably their faith. The church was the focal point of the spiritual and social life of a community whose Catholicism was as much a part of their individual and collective identities as was their Irishness. One of their most immediate concerns as a community had been the establishment of a church and the procuring of a resident priest. People looked to the parish priest for leadership and guidance, not just in religious matters but temporal ones as well. From the outset, the settlement was blessed with strong, competent, spiritual men in that position, and the idea of pastor as leader was reaffirmed. In many cases, they looked upon him with fatherly affection.

As with any group of people, leaders emerged, entrepreneurs took advantage of opportunities, and through hard work or good fortune, or both, men prospered. The community began to acquire the trappings of civilized society, and a social hierarchy began to take shape.

Freed from the struggle for mere survival, more and more people became interested in broadening the community’s economic, political and cultural horizons. Many of the original settlers were literate, educated men and women; many others, though lacking in formal education, emerged as natural leaders. They got involved in agricultural organizations and latched on to new developments and ideas. They were instrumental in bringing in electricity and telephone service, and were the driving force behind many of the social activities that took place. They founded organizations like the Ancient Order of Hibernians, the Johnville Debating Society, the Total Abstinence Society and the Self-Determination for Ireland League.

For some however, life on the farm lost its appeal or simply became too much of a struggle. Out-migration, particularly to neighbouring Maine, was always a factor but it became more prevalent with each succeeding generation. Those lacking the physical stamina, determination, or aptitude simply left for greener pastures. The reality fell too far short of the dream. For others, the life simply did not meet their needs.

The marble tablets and granite obelisks that stand in the shadow of the Johnville church are silent testimony to the strength and courage of those that endured, but the men and women they commemorate were not stone, but flesh and blood. They came great distances in search of a dream, leaving behind them all that was familiar and loved.

Young men and women, buried here, once gazed from the deck of a ship on aged mothers and fathers they knew they would never see again. Staring into a fire at the end of a sixteen-hour day, farmers remembered the feel and smell of the earth they tilled far away and long ago. Murmuring age-old prayers and remembered fragments of verse, they ached with yearning for family and friends.

Humming familiar refrains of melancholy lullabies, mothers rocked their babies and saw again mist-enshrouded hills and crooked stone fences, smelled peat fires, and heard the sickening thud of the evictor’s battering ram and the sound of marching feet in the night. Some could recall the pangs of a hunger so intense they clawed at the grass beneath their feet.

Take a walk through this old cemetery some wind-whipped September afternoon. Caress the rough stone and trace the outline of the worn inscriptions. Feel the pull of posterity. Sometimes, if you’re lucky, you can reach across the generations and touch, not just hand to stone, but soul to soul.

___________________________________________________

[1] W.P. Kilfoil, Johnville, The Centennial Story of An Irish Settlement, Fredericton, Unipress, 1962, p. 14-15.

Reference

Kilfoil, W.P., Johnville, The Centennial Story of An Irish Settlement, Fredericton, Unipress, 1962

Church socials provided the community’s fiddlers, storytellers, step-dancers, thespians and

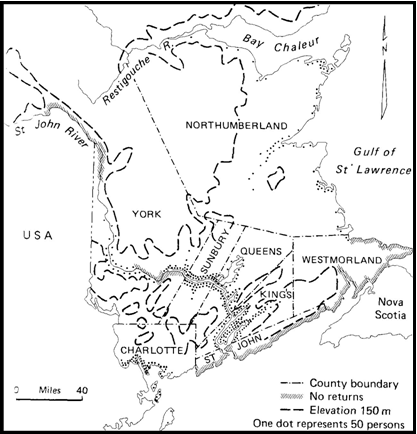

Population Distribution in New Brunswick, 18516

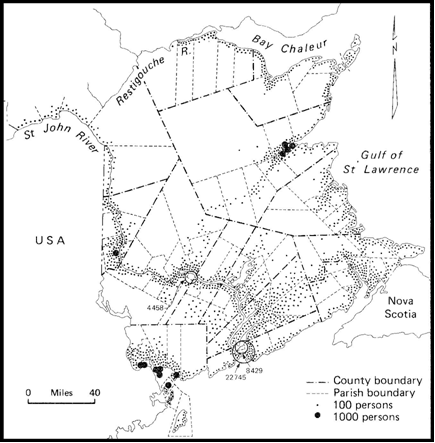

Population Distribution in New Brunswick, 18516