Grand Falls Museum

Grand Falls Museum

Grand Falls Museum

68 Madawaska Road

E3Y 1C6

Contact person: Anne Côté

Phone: (506) 473-5265

Fax : (506) 475-7755

Out-of-Season, by appointment, phone: (506) 473-4881 or (506) 473-5940

Hours of Operation:

The Museum is open from the 3rd week in June to the last week of August from Monday to Friday from 10AM to 5PM. To access it, take exit 75 from the Trans Canada Highway.

The museum contains several references of genealogical interest:

Jean-Guy Poitras, “Répertoire des marriages au Nord-Ouest du Noveau-Brunswick, Canada pour les comtés de Madawaska, Restigouche (partiellement) et Victoria”. This compilation of marriages for northwestern NB is from 1792-2001 and includes mostly Catholic marriages.

Early marriages and baptisms of Van Buren, Maine (most early marriages for this region were recorded in the Van Buren register)

A collection of obituary and mortuary cards

Several local histories

Genealogical anthologies and family trees – not well-documented but still of interest. If anyone wants a copy made of this material, they should contact the compiler. Visitors are welcome to write out by hand information from these resources.

The following families are included:

Albert, Armour, Baker, Barriault, Blunden, Boucher, Boyer, Briggs, Brown, Budrow, Burgess, Butterfield, Caldwell, Carroll, Chase, Costigan, Côte, Cowett, Curless, Curran, Currier, Currier-Duston, Davis, DeMerchant, Desjardins, Dixon, Everett, Fraser, Gagnon, Gamble, Gaunce, Gauvin, Gillespie, Godbout, Goguen, Grant, Green, Gueret dit Dumont, Hallett, Hartsgrove, Hartt, Hathaway, Hianvew, Hillman, Hitchcock, Holmes, Horseman, Hudson, Jean, Jenson, Jovin, Kinney, Koven, Labrie, Lagacé, Lebel, Leclerc, Levesque, Long, Lynch, McCann, McCluskey, McCooey, McCormack, Mclaughlin and Allingham, McLaughlin and Campbell, McLaughlin and Delahenty, McLeod, McManus, McMillan, McQuade, Michaud, Mockler, Mulherin, Murphy, Newcomb, O’Neill, O’Regan, Ouellet, Ouellette, Page, Pelletier, Pine, Poitras, Powers, Price, Quigley, Rasmussen, Reed, Rideout, Rossignol, Rouleau, Roy, Sisson, Slye, St-Laurent, St-Pierre, Stroupe, Tompkins, Toner, Turcotte, VanderBilt, Vandine, Warnock, Watson, Wharton, White, Williams, Wiswall, Woodward and Woolsey.

There are also materials of interest at the local Grand Falls Public Library:

Transcriptions of Census Records for Victoria and Madawaska Counties – 1851, 1861, 1871, 1881, 1891, 1901

Transcriptions of baptisms and deaths for several Madawaska parishes

The Pierre-Albénie Collection (for south-eastern Québec and north-western NB (with a few Irish entries)

Donations are welcome.

Grand Falls Museum

Grand Falls Museum

Grand Falls Museum

68 Madawaska Road

E3Y 1C6

Contact person: Anne Côté

Phone: (506) 473-5265

Fax : (506) 475-7755

Out-of-Season, by appointment, phone: (506) 473-4881 or (506) 473-5940

Hours of Operation:

The Museum is open from the 3rd week in June to the last week of August from Monday to Friday from 10AM to 5PM. To access it, take exit 75 from the Trans Canada Highway.

The museum contains several references of genealogical interest:

Jean-Guy Poitras, “Répertoire des marriages au Nord-Ouest du Noveau-Brunswick, Canada pour les comtés de Madawaska, Restigouche (partiellement) et Victoria”. This compilation of marriages for northwestern NB is from 1792-2001 and includes mostly Catholic marriages.

Early marriages and baptisms of Van Buren, Maine (most early marriages for this region were recorded in the Van Buren register)

A collection of obituary and mortuary cards

Several local histories

Genealogical anthologies and family trees – not well-documented but still of interest. If anyone wants a copy made of this material, they should contact the compiler. Visitors are welcome to write out by hand information from these resources.

The following families are included:

Albert, Armour, Baker, Barriault, Blunden, Boucher, Boyer, Briggs, Brown, Budrow, Burgess, Butterfield, Caldwell, Carroll, Chase, Costigan, Côte, Cowett, Curless, Curran, Currier, Currier-Duston, Davis, DeMerchant, Desjardins, Dixon, Everett, Fraser, Gagnon, Gamble, Gaunce, Gauvin, Gillespie, Godbout, Goguen, Grant, Green, Gueret dit Dumont, Hallett, Hartsgrove, Hartt, Hathaway, Hianvew, Hillman, Hitchcock, Holmes, Horseman, Hudson, Jean, Jenson, Jovin, Kinney, Koven, Labrie, Lagacé, Lebel, Leclerc, Levesque, Long, Lynch, McCann, McCluskey, McCooey, McCormack, Mclaughlin and Allingham, McLaughlin and Campbell, McLaughlin and Delahenty, McLeod, McManus, McMillan, McQuade, Michaud, Mockler, Mulherin, Murphy, Newcomb, O’Neill, O’Regan, Ouellet, Ouellette, Page, Pelletier, Pine, Poitras, Powers, Price, Quigley, Rasmussen, Reed, Rideout, Rossignol, Rouleau, Roy, Sisson, Slye, St-Laurent, St-Pierre, Stroupe, Tompkins, Toner, Turcotte, VanderBilt, Vandine, Warnock, Watson, Wharton, White, Williams, Wiswall, Woodward and Woolsey.

There are also materials of interest at the local Grand Falls Public Library:

Transcriptions of Census Records for Victoria and Madawaska Counties – 1851, 1861, 1871, 1881, 1891, 1901

Transcriptions of baptisms and deaths for several Madawaska parishes

The Pierre-Albénie Collection (for south-eastern Québec and north-western NB (with a few Irish entries)

Donations are welcome.

A Hard Life Surely: The Role of Women in Rural Irish Communities

“A man may work from sun to sun,

There was a time in Ireland when women were not only equal to men – but also highly revered and respected. Centuries of Christianity and its patriarchal ministrations had reduced woman’s place in society to one of subservience and submissiveness.

By the 19th century and the age of emigration, the division of labour on an Irish farm was hardly equal and favoured men entirely. Men’s responsibilities – preparing the field for sowing, harvesting, peat gathering and farm repairs hardly equalled women’s responsibilities which included planting and tending the crop and animals, gathering the crops, preserving the crops, feeding and clothing and tending the family, plus the inconveniences of child bearing and all that inferred. Men, without question, had more leisure time than women. This pattern would cross the sea with the wave of emigration in the first half of the nineteenth century and be exasperated by the difficult life of backbreaking homesteading tasks awaiting an Irish family in the New World.

Most Irish communities in New Brunswick were tucked away on lands that were isolated from the rest of the colony’s established society. This isolation led to subsistence farming based on self-sufficiency – most things were produced on the farm for home consumption and very little was sold or purchased for their needs.

“A backwoods farm,” wrote an English observer, “produces everything wanted for the table, except tea, rice and salt and spices. To the list of supplementals could be added occasional dry goods, shoes and metal for farm implements.”1

This statement certainly holds true for the early Irish settler farms in New Brunswick. William Dunn, of Melrose purchased very little for his family over a six-month period at a local general store in 1899. His account listed figs of tobacco, moccasins, oats, seed potatoes, a harness and county taxes ($1.66).2

As families settled into a farming lifestyle throughout the New Brunswick wilderness, a true division of labour developed and men and women performed different tasks on the family farm. Farmers worked by the seasons – and the number of daylight hours regulated a workday.

By no means were men the ‘breadwinners’ of this economy. Both women and men actively participated in the production of family subsistence…indeed women were engaged in from one-third to one-half of all food production on the farm. Of the farm staples – milk, meat, vegetables, and eggs – women produced the greater numbers of products and division of labour. Women were also likely to be found helping men with their portion at peak planting time [plus] all the household work and care of the children. To be sure, men and women alike worked hard to make their farms produce. But one cannot avoid being struck by the enormousness of women’s workload.3

Also, where men generally only worked in daylight, women continued to work well into the evenings despite poor light in the farmhouse.

The unequal division of labour is easily seen when the list of “woman’s chores” is reviewed.

Outside of the farmhouse, women were responsible for:

– Planting, tending and harvesting of the kitchen garden.

– Assisting with the seeding and harvesting of grain crops.

– Maintaining the henhouse, including feeding hens, collecting eggs and slaughtering chickens.

– Maintaining the dairy including the milking, and feeding of the cows.

– Gathering of wood from the woodpile.

– Threshing of buckwheat, corn and flax.

Inside the farmhouse, women:

– Prepared, preserved, and cooked all farm produce, including jams, pickles, but also butter. Most preserving occurred during the hottest months of the year and required a very hot stove for sterility purposes.

– After slaughtering, prepared cuts of meat – either by smoking, drying or salting and made sausages.

– Had the complete responsibility for the manufacture, care and repair of family clothing. This included creating homespun cloth as well as spinning and carding wool for knitting and patching and reshaping worn clothing, blankets and bed ticks (mattresses).

– Making of homemade lye soap and tallow candles.

– Responsible for bringing water in from outside wells – a backbreaking task on Monday washing day and tediously difficult at the best of times.

– Also responsible for all household chores – from simple housecleaning and family meals to laundry, and even removing ashes from the stove and fireplace.

– Supervision and schooling of children.

A farmer was said to be a ‘jack of all trades’. But women’s work outdistanced men’s in the sheer variety of tasks performed. Add to this the added burden of childbearing. It is no surprise that women suffered so many stillbirths and miscarriages during the pioneer years.

There was an added factor which certainly came into play for Irish women in New Brunswick communities. Subsistence farming was okay for daily food requirements but some monies still had to come in to the household for other necessary items. To acquire this much needed extra cash, men often worked away from the farm for long periods at a time – leaving the women at home to cope with all of the farm chores – adding her husband’s chores to her own already taxing duties.

Mary (Murphy) Hennessy lived on McLaughlin Road, about 10 km north of Moncton, near Irishtown. Isolated, she also carried the burden of the farm work on her own for much of the year. In 1908, she wrote in her journal that her husband Jim was away in January and came home in February ‘to insulate the walls [on the new house]. He then ‘left 2 March and worked in Moncton’. He was ‘home for a week in June to help put in the crop” and he left again. And then she noted ‘Jim home three weeks in August and started back to work [in Moncton] 31 August. [He was] through work the first week of November.4

Isolated from family, friends and even close neighbours, Mary Hennessy’s husband was only home for 8 weeks from January to November that year – and she with two small children to care for as well.

Nor is this an isolated case. In many homes, this way of life was indeed the norm. Except in planting and harvesting seasons, men were away for several months at a time. An examination of the parish records for Irishtown births throughout the from 1890 to 1910 show a significant rise in births nine months after the planting season and again nine months after harvest. In the months in-between there are significantly fewer births.5 Clearly, the men were away from home more than they were home.

Running the farm by themselves was indeed challenging. However it was loneliness bred from the isolation that truly preyed on their minds. Adapting to this new isolation was particularly difficult because in Ireland, these women lived in close-knit neighbourhood communities – clusters of houses densely packed together and filled with family and friends – and this network of social contact was especially important when times were tough.

In pioneer communities in New Brunswick farms were surveyed out in 100-acre lots or more and neighbours were a good distance away – especially through long winter nights. Catherine Parr Trail, speaking of the experience in Ontario said:

“One of our greatest inconveniences arises from the badness of our roads, and the distance at which we are placed from any village.”6

Isolation bred loneliness and loneliness bred cabin fever or out-right insanity. Nearly every community had someone who would be jokingly referred to as a “Batty Betty”. Left to their own devises on the homestead while the men were away for months at a time took incredible strength and most did manage the stress and difficult way of life but it couldn’t have been easy. Children, raised almost exclusively by their mothers, generally held their mothers in high regard – all the days of their lives. Their fathers, they barely knew at all.

Disease and death took their toll in most of these communities as well. When one’s wife died, husbands usually quickly remarried to provide stability to the family. Those that did not remarry barely coped. One keen observer of the day labelled it “frenzied grief”.

“ [In Johnville] a poor fellow had become mad, his insanity attributed to the loss of his young wife, whose death left him a despairing widower with four infant children. He had just been conveyed to the lunatic asylum, and his orphans had already been taken by the neighbours, and made part of their families.”7

The difficulties faced by women in the pioneer Irish communities can be easily understood by studying any family where death visited and took a spouse. Sara Donahoe of Irishtown married John McKelvie of Memramcook in 1881. They were married for 14 years when he was accidentally killed by a train in Memramcook in 1895. By this time, Sara had already given birth to seven children and three had died in infancy. She then married Richard Anketell of Tankville six years later and had six more children over an eight-year period.8

Life was not all drudgery and hard labour in these isolated Irish communities. Winters provided the best road conditions – frozen roads and fields shortened the journey by sleigh. Weddings often occurred in the winter months – because that was the only ‘down-time’ on a farm. Also, visitors often came at this time of the year as well and sometimes stayed for long periods of time. Women also gathered in winter for quilting bees and socials – weather permitting. But most winters were long and lonely. Mary Hennessy’s diary is often preoccupied with three items through the lonely winter months – weather, cold and road conditions. Summers were often too busy for socializing but after the harvest was in, there were ‘basket socials’ to raise money, or numerous dances – often held in a neighbourhood home or the local school. Women looked forward to church activities not only because they were devoted to their faith, but also as a means of socialization. Mary Hennessy noted in her journal in 1907 that she was depressed because mass – only said every third Sunday of the month – had been cancelled three months in a row because of bad weather and a smallpox scare.9

Life was indeed trying for pioneer Irish women as they carved out a place for themselves in the new colony. It was a difficult life. Despite the drudgery, life was still cherished. Despite the problems, depravities and loneliness, life was still ten times better here in the colony compared to the life they would have led as a tenant farmer’s wife in Ireland.

Mrs. Creehan, originally of Galway, settled in Johnville and was interviewed by British MP John Francis Maguire in 1868. She and her husband were tenant farmers and had been pushed off their land by their landlord in Galway. When asked about her life here she said:

“Thrue for you, sir, it was lonely for us, and not a living soul near us.”

The interviewer continued, asking, “But Mrs. Creehan, I suppose you don’t regret coming here?” And she responded:

“’Deed then no, sir, not a bit of it…we have plenty to ate and drink…and no one to take it from us…And, sir, if you ever happen to go to Galway and see Mr. _______, [the landlord] you may tell him for me…in my mind, t’was lucky the day he took our turf and the sayweed.”10

Mrs. Creehan was speaking of her own experiences but in many ways she spoke for most pioneer women in Irish communities throughout New Brunswick.

__________________________________________________

[2] The storeowner was also the local tax collector. J.D. Lane, Accounts Book, General Store, Bayfield NB, Unpublished, 1895-1902.

[3]Farragher, p. 59.

[4] Mary Hennessy, Personal Diary, Unpublished 1881-1953.

[5] ______, Parish records, St Anselme Roman Catholic Church and St Bernard’s Roman Catholic Church, Moncton.

[6] Catherine Parr Trail, The Backwoods of Canada, Toronto, McClelland & Stewart, 1966, p. 53.

[7] John Francis Maguire, MP, The Irish in America, London, Longmans, Green & Co, 1868, p. 68.

[8] Birth, marriage and death records, St Anselme and St Bernard’s parishes – various entries.

[9] Mary Hennessy, Personal Diary, Unpublished 1881-1953.

[10] John Francis Maguire, p. 62.

John Mack Farragher, Women and Men on the Overland Trail, New Haven, Conn., Yale University Press, 1979, p. 45.

______, Birth, Marriage and Death records, St Bernard’s Roman Catholic Parish, Moncton, NB. Microfilm, Centre d’Études Acadiennes, Librarie Champlain, Université de Moncton.

Farragher, John Mack, Women and Men on the Overland Trail, New Haven, Conn, Yale University Press, 1979.

Hennessy, Mary (Murphy), Personal Diary, Unpublished 1881-1953.

Lane, J.D. Account Book, General Store, Bayfield NB, Unpublished, 1895-1902.

Maguire, John Francis, MP, The Irish in America, London, Longmans, Green & Co, 1868.

Trail, Catherine Parr, The Backwoods of Canada, Toronto, McClelland & Stewart, 1966.

The Evolution of Irish Cuisine

By Shauna Driscoll

When we think of Irish culture, and especially Irish cuisine, one particular image usually springs to mind; that of the Irish farmer cultivating his potato crop to ensure a bountiful fall harvest. In fact, this image could not be further from the truth.

While the potato certainly has become a hallmark of Irish tradition, it is a relatively new produce for the Irish, and is in fact not native to their lands. This root vegetable was brought to Ireland from South America during the mid-17th century. It is only in the past few hundred years that the potato has become the icon of Irish heritage that we see today.

Since its introduction the potato quickly became a staple food item among the poor classes, due mostly to its ease of growth and storage, its heartiness in the often poor Irish soil and the many essential vitamins it was able to provide to the daily diet. This trend still exists today in traditional Irish dishes like colcannon and boxty. But, what was their diet like before this new foodstuff came into their possession?

Further back in history the Irish subsisted mostly on large and small game animals, and other products readily found throughout their territories. Deer, for instance, would be cooked within large holes cut in the ground that were filled with water. The water was then heated by the introduction of hot stones, and the meat boiled in a long process throughout the day.

Smaller game animals were frequently roasted over fires. In the earliest known histories, poultry was covered in a thick coating of clay, skin and feathers intact. The clay wrapped poultry was then placed into the fires until the clay was baked into a solid covering which was broken and peeled away, bringing the feathers and skin with it and exposing the moist meat within.

As production methods grew more organized, cattle, sheep and pigs were raised to feed the burgeoning population. However, these sources of food were mostly reserved for the higher classes who could afford such things, leaving the poor to make do with milk, butter, cheese and offal (the edible, mainly internal organs of an animal), often complimented by oats and barley, and a wide range of wild nuts and berries. In earlier times it is believed seeds of knotgrass and goosefoot may have been used to make porridge as a hot, sustaining meal.

With the introduction of the potato the poorer classes now had an easy crop that was useful in a variety of ways. Supplemented with buttermilk it formed the basis of the Irish diet, and it was also useful in fattening pigs that would be slaughtered and then cured for winter storage.

Unfortunately, this reliance on the potato crop also meant that a poor season would affect those classes more severely, leaving them starving and unable to sustain themselves throughout the winter months. And it was during one of these times, the Potato Blight of 1846 – 1849, that approximately 2 million Irish citizens emigrated from their homeland in an effort to find better fortunes abroad.

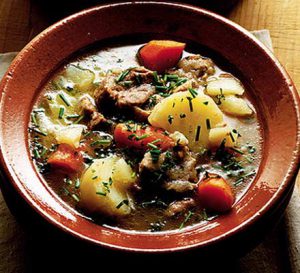

Traditional Irish Stew

These emigrants brought with them their signature cuisine and cooking style, although not everything could remain as it was. Irish Stew, for instance, is made solely from lamb or mutton meat. Sheep were widely raised for wool clothing, milk for drinking and cheeses, and later used as a food item along with other easily found or grown ingredients.

Once they reached the New World the Irish were not able to continue all of these traditions. Foodstuffs that grew plentiful, or were raised easily, like sheep, were not readily found in America. Over time their traditional dishes had to change and evolve to include the native plants and animals.

Corned Beef and Cabbage Dinner

A prime example of this, the traditional Easter supper in Ireland most commonly consisted of boiled bacon and cabbage, as pork was more readily available to the poorer classes than any other meat product. In America the traditional Easter supper of those poor emigrants who found their way to the New World was adapted to the new environment they found themselves within. With beef, especially the poorer cuts which were tenderized by “corning” them in a brine solution, being the more prominent and less expensive meat source, the traditional boiled dinner became the one now associated with St. Patrick celebrations in North America: corned beef and cabbage.

We continue to see the evidence of this Irish emigration throughout out modern culture in North America. The large influx of Irish in the 18th and 19th centuries has had significant influence not only on North American cuisine but also on the assortment of celebratory drinks we gained from other cultures to have arrived in the New World.

Bunratty Mead

One of the oldest alcoholic beverages to be produced in the world comes from Ireland in the form of mead, a honey wine traditionally served before the start of a meal and to end a feast. It was a common addition to any celebration and festival, and was used as a gift for newlyweds. An offering of a month’s supply of mead (one full lunar cycle) was thought to bring good fortune to the couple. This practice is believed to have led to the well-known idea of a couple being on their ‘honeymoon’ bearing with them a sweet honey wine for the duration of an entire lunar cycle.

Coming from an often damp country, the Irish are also well known for developing other spirits and liquors that were either served on their own, or mixed with a variety of different cold and hot beverages to chase away the chill. Mulled wines, whiskey and ales were most commonly found for such purposes.

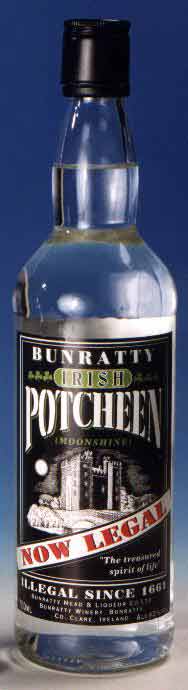

Bunratty Potcheen

For those who couldn’t afford such luxuries as whiskey and wine, the ever industrious and ingenious Irish found a way to make their own out of a fermentation of potatoes. The result of this process, “potcheen”, is now made commercially however it doesn’t carry quite the same “kick” as the home-made variety still being clandestinely produced in some of the more isolated regions of Ireland.

At some point during the 1940s, a group of American travelers arriving at the Shannon International Airport on a miserable winter evening were treated to an Irish coffee, a beverage created on the spot in an effort to warm the weary group. It quickly made its way to San Francisco, a city that shares similarities to the Irish climate, and has since spread as a popular drink in North American restaurants.

Two of the most common potato dishes that have traveled across the Atlantic with the Irish are boxty, a savory pancake made with potatoes and onions, and colcannon, a wonderfully comforting Irish dish that includes mashed potatoes, cabbage and onions. Although it may not be authentically Irish, I also include bacon in my recipe for colcannon. Here are recipes that you can try for a little taste of Irish cuisine.

Ingredients:

– 1/2 pound raw potatoes

– 1/2 pound leftover, unseasoned mashed potatoes

– 1 mdeium onion, finely chopped

– 1/2 pound flour

– 1 egg, slightly beaten

– salt and pepper to taste

– milk

Preparation:

Mix the grated and mashed potatoes with the onion. Stir in the flour and egg. Preheat lightly greased griddle or frying pan. Add enough milk to potato mixture for a thin enough batter that will drop from a spoon.

Use a 1/4 cup measurer to spoon out batter onto griddle. Grill for 3-4 minutes on each side.

They can be served with tart applesauce or as part of an Ulster Fry with bacon, fried sausage, fried eggs, and black pudding and soda bread.

Ingredients:

– 3 pounds russet potatoes

– 1 Tbsp. olive oil

– 1 small onion, diced

– 2 cloves garlic, minced

– 3 cups shredded cabbage (or kale)

– kosher salt and pepper to taste

– 1/4 cup butter, divided

– 1/3 cup half and half

– 2 slices pre-cooked bacon, warmed according to package directions and crumbled

Preparation:

Peel and dice potatoes. Place in a large pot and cover with water by one inch. Bring to a boil, covered, over high heat.

Remove cover, reduce heat to medium, and allow potatoes to cook 12-15 minutes, until tender when pierced with a fork.

Meanwhile, heat olive oil in a large skillet. Add onion and garlic. Cook, stirring occasionally, until onion is softened, about 3 minutes.

Add cabbage, season with salt and pepper, and cook until soft, about 5 minutes.

Drain potatoes and return to pot. Season with salt and pepper. Add two tablespoons of the butter and the half and half. Mash.

Fold in the cabbage mixture and the bacon. Top with the remaining butter. Serve immediately.

Summary:

Undoubtedly there are many cultures that have helped to shape our North American history, but perhaps one of the strongest influences of them all can be traced back to Irish immigrants, who hoped to make a better life in the New World. We see the markings of their contributions through so many of our own traditions: hearty soups and stews; boiled dinners; hot drinks served with liquor to take the chill off cold bodies during long winters; the ‘honeymoon’ time for newly married couples.

It is a mark that has seeped deep into our common heritage as we continue to build our identities apart from our ancestral lands. It brings with it a sense of comfort and well-being. And it has helped to ensure that even when we settled so far away from our people, we still managed to bring with us a piece of home.

_________________________________________________

Bibliography

A History of Irish Cuisine – www.ravensgard.org/prdunham/irishfood.html

Wikipedia – en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irish_cuisine

Great Food – www.greatfood.ie

Wikipedia – en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irish_coffee

Recipes – www.about.com/food

The Irish Language in New Brunswick

By Marilyn Driscoll

Language – for many people it is not just the means by which aspects of their ethnicity are handed down to their offspring, and by them to subsequent generations, but it is the very substance of their culture. In the study of linguistics and anthropology, the first step in the extinction of a language is considered to be when it is no longer spoken by the children of that ethnic identity.

“The overwhelming majority of the millions who reached Canada and the United States from Ireland in the last century [19th] and, of course before that, were Irish speakers on arrival, a large proportion of them being monoglot Irish speakers at that.”[i]

“It appears that in the eighteen-thirties and forties there were many small Irish-speaking communities in isolated areas and along the New Brunswick and Maine frontier but there is hardly a trace to be found of this today.”[ii]

Indeed, as we made our way into the 20th century it was believed that there were no Irish speakers left in New Brunswick at all. However, take one look at the 1901 census of the Province of New Brunswick and quite another story is told. The 1901 census is the only one we have available that specifically asks the question of mother tongue, and further defines it as being a language that is still being commonly spoken in the home at the time. Here we find not one, not two, but several individuals as well as a scattering of families who still list Irish as being the tongue they first learned and is still being spoken in their homes. Other than their language, they have little else in common. A detailed and methodical study of the Irish language issue in New Brunswick is currently being undertaken by noted Irish scholar Dr. Peter Toner. His findings will be published in the reasonably near future and are sure to hold surprising information for those of us who believed that the Irish language was left behind when our ancestors left their homeland for North America or, at the very least, was dropped as soon as they arrived.

Time and again history has shown that it is far more likely that immigrants to a new country will retain their old cultural values and customs and will speak their mother tongue when they are part of a larger community of their compatriots, regardless of their level of comfort with the predominant language of their adopted country. With such a support group around them, immigrants are eager to preserve their own heritage, which includes not only customs and traditions but also language. Without it, the goal of every immigrant would have been to master English quickly. “English was the passport to basic status and security; Irish was the badge of foreignness and poverty.”[iii]

‘With the historic British domination of Ireland, Irish was almost lost to English – the language of advancement. Likewise, when Irish-speaking immigrants left for the New World, they essentially left their native tongue behind in their native land and became assimilated into the English-dominated culture, said Concordia history Professor Ronald Rudin.

“English was the language of advancement and if you were going to learn one language, then you might as well learn English. So they may have shared a religion with the French, and they may have gotten along with them because of their shared religion, but the language… they learned was not the language of the majority, but of the minority who held economic power.”

As a result, he said, Irish quickly disappeared in the new world.’[iv]

Not everyone was happy to let the Gaelic languages die in Canada. On Friday, the 21st of February, 1890, Senator Thomas Robert McInnes, a descendent of Highland Scots, introduced to the Senate, a Bill entitled An Act to provide for the use of Gaelic in official proceedings. In support of his Bill, McInnes quoted facts from the 1881 census that showed that “Canadians of Gaelic origin, Irish and Scottish, outnumber those of French origin by nearly 400,000 and constitute more than one-third of the entire population of Canada.”[v]

Although the motion for a second reading of this Bill would be defeated by a vote of 42 to 7, in supporting the Bill through its first reading, McInnes brought forward several interesting arguments:

· of the entire Canadian population of the day (4,324,810), the census figures show the English in third with a population of only 881,301. Canadians of “Gaelic origin” – Irish and Scots tallied together, held first place at 1,657,266, followed by the French at 1,298,929. In a distant fourth place with 254,319 were the persons of German origin. No mention is made of the Welsh who, though of “Celtic origin” spoke a Celtic language as different from the Irish and Scottish Gaelic as French is from German.

· In support of his Bill, McInnes also quoted from a speech given by none other than Sir John A. MacDonald in the House of Commons on the 17th of February 1890, in opposition of a Bill to abolish the language rights of French-Canadians, the sentiment of which could be applied equally to the Gaelic languages in Canada:

“Why, Mr. Speaker, if there is one act of oppression more than another which would come home to a man’s breast it is that he should be deprived of the consolation of hearing and speaking and reading the language that his mother taught him. It is cruel. It is seething the kid in his mother’s milk.”[vi]

· According to Senator McInnes, in 1890 the Canadian Senate contained “ten Highland Scotch representatives…that can speak more or less Gaelic; we have eight Irishmen that can speak more or less Gaelic, making in all over twenty members of this House who are Scotch and Irish Celts, and thirty-two members of the Commons who speak Gaelic and Erse to some extent.”[vii]

While the Bill itself was defeated, this public action by Senator McInnes was an early indication of the change in attitude that was to come in the latter part of the 20th century and continues to swell, not only in Canada, but in all parts of the world affected by the Irish Diaspora. Finally, after centuries of feeling like second-class citizens and renouncing their customs, culture and language in order to fit in, the Irish are embracing their heritage once again – and others are paying attention. Not only is there light at the end of the tunnel, but it appears to be a beacon, attracting more and more people of Irish descent back to a language previous generations had turned their back on.

The Irish, once relegated to the worst lots of land and the worst jobs available, are now seen in every walk of life, at every level of society. In a complete reversal of pre-20th century attitude, in 1997 Dr. Gus Gorman, the head of radiology at the Montreal Children’s Hospital, and a teacher of Irish, is quoting as saying:

“Ireland’s most authentic badge of honour is its language. “I suppose that the only distinctive thing about us is that we have a language other than English, because we all basically look the same and we’ve all given up whatever religion we had. There’s not much to distinguish us, unless you identify the music, the dancing, and, of course, the most authentic badge of Irishness is really the language.”

While the Irish language may have disappeared quite quickly in the New World, it was not before it left its mark on the English language. Dr. Gorman said Irish people have practically “re-invented” the English language.

“It’s far more entertaining and it has far more flair and inventiveness as a result of how things are said in Irish.”

“Putting the kibosh on something,” for example, comes from the Irish phrase which means “cap of death.” Slew comes from the Irish word for crowd. And of course, whiskey comes from the Irish for “water of life.”

“The Irish way of speaking English was one of the richest gifts brought to Canada by any immigrant group.”

“…Irish syntax, carried into English, is capable of far greater precision than that of standard English, and may help to explain why so many of the greatest writers in English in the past three centuries have been Irish.”[viii]

The renewed interest in the Irish language is clearly shown by the number of language classes that are offered in most major cities in North America. No matter which of the three Irish dialects a person may be interested in learning: Ulster; Connacht (also sometimes referred to as Connemara); or Munster, there are lessons available, either on-line or through books and tapes, locally or directly from Ireland. So, if you’ve always wondered about the language of your ancestors, there’s no time like the present to start learning it yourself. The Irish culture will surely thrive when Irish descendents around the world pay tribute to their ethnicity by proudly wearing that most “authentic badge of honour” – the language of their ancestors.

So, on a somewhat related topic, with the renewed interest in all things Irish, perhaps this essay should end by answering the one question that is most frequently asked: “Is it pronounced [K]eltic or [S]eltic?”

According to the website at www.ibiblio.org/gaelic, the term “Celtic” came from the Greek word for “barbarian”: Keltoi.

“It is from the greek Keltoi that Celt is derived. Since no soft c exists in Greek, Celt and Celtic and all permutations should be pronounced with a hard k sound [underlining added for emphasis].

It is interesting to note that when the British Empire was distinguishing itself as better and separate from the rest of humanity, it was decided that British Latin should have different pronunciation from other spoken Latin. Therefore, one of these distinguishing pronunciational differences was to make many of the previously hard k sounds move to a soft s sound, hence the Glasgow and Boston Celtics. It is the view of many today that this soft c pronunciation should be reserved for sports teams since there is obviously nothing to link them with the original noble savagery and furor associated with the Celts. [underlining added]”

This could explain why the soft s pronunciation is far more common among those of Scottish ancestry who, by very definition, have their pasts rooted more firmly in the British Empire whereas the Irish, even after nearly of century of self determination, still feel strongly about retaining the original pronunciation.

[i] The Untold Story: The Irish in Canada, Volume II:– Edited by Robert O’Driscoll and Lorna Reynolds: Pg 711 – Reflections on the Fortunes of the Irish Language in Canada, with some reference to the fate of the language in the United States – by Proinsias Mac Aonghusa

[ii] Ibid, pg 712

[iii] Ibid, pg 712

[iv] Out of Ireland series published by the Saint John Times Globe from June 9th to July 25, 1997- Issue 11: Irish stalwarts determined to teach ‘this weird and wonderful language’ – by Mia Urquhart

[v] The Untold Story: The Irish in Canada, Volume II:– Edited by Robert O’Driscoll and Lorna Reynolds: pg 720 – An Attempt to Make Gaelic Canada’s Third Official Language – by John Ward

[vi] Ibid, pg 721

[vii] Ibid, pg 721

[viii] The Untold Story: The Irish in Canada, Volume I:– Edited by Robert O’Driscoll and Lorna Reynolds: pg 184 – Newfoundland and the Maritimes: An Overview – by Kildare Dobbs

O’Driscoll, Robert, and Reynolds, Lorna, The Untold Story: The Irish in Canada, Volumes I and II, Published by Celtic Arts of Canada, Toronto, 1988. Printed in Canada by John Deyell, Willowdale, ON

Urquhart, Mia, Irish Stalwarts Determined to Teach This ‘Weird and Wonderful Language’ [online], Retrieved 22 February 2008 from: http://personal.nbnet.nb.ca/rmcusack/Story-23.html